The idea of ??the power and importance of public opinion has always been an important part of what we call ‘modernity’. We find classic early formulations of writers like John Locke – a pioneer in equal measure both to the Enlightenment and to liberalism, and a resolute defender of The Glorious Revolution in England of 1688. In his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding of 1690, Locke gives a first formulation of the idea that public opinion has a kind of moral authority.

Moral good and evil, Locke concludes, lie in our compliance or lack of compliance with any given law, a law where the related rewards or punishments come to us from the legislature.

There are three different kinds of law that interest Locke: there is divine law, legal law, and there is what Locke calls ”the law of opinion or reputation” (Book II, Chapter 28, 7-13). This provides a measure by which virtues and vices are assessed; it awards people either standing or blame and, in Locke’s thinking, over the state and politics it has a significant role. Through Locke’s famous ‘social contract’ people hand over a large portion of their rights and freedoms to a sovereign. The sovereign takes the power to punish, and it becomes no longer possible to take the law into one’s own hands against miscreants. But the people still have the possibility of moral sanction, emphasises Locke: ”However, they still retain the power to think ill or well, and to like or dislike the behaviour of those they live among and interact with: and by this approval or disapproval establish those among them that they call virtuous and immoral.”

Locke’s ideas met with criticism in their time. “Is not the natural law, which makes virtues of virtues and vices of vices, eternal and unchanging?” asked his critics. Locke was quick to reply that he by no means intended to make public opinion the arbiter of good and evil, just saying that it actually does so in social reality. Locke, in this sense, floated around the subject. But what is clear, however, is that he wrote about public opinion’s moral legitimacy and importance, which had not previously been acknowledged.

One hundred years from then, we can see how the doctrine of ‘public opinion’ has evolved into a new idea of ??‘the public’. A classic formulation is available in a text by Immanuel Kant. It bears the title: Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? (BeantwortungderFrage: WasistAufkläring?) and was published in 1784. Kant does here what his title promises, namely to answer the question. The philosopher writes:

“Enlightenment is man’s leaving his self-inflicted pupilage. Pupilage is the inability to make use of his understanding without direction by someone else. Self-inflicted is this pupilage, not for a lack of understanding, but a lack of determination and courage to make use of this understanding without another’s guidance. Sapereaude! Have the courage to make use of your own understanding, reads thus the Enlightenment’s motto.”

But, for enlightenment in this sense, freedom is required. Kant argues:

”For this enlightenment, nothing more is needed than freedom, and more specifically the most harmless of all that can be accommodated under the generic heading of freedom: the freedom to do according to all public use of his reason. [—] But by the public use of one’s own reason I mean that use that someone makes of it as a scholar before the entire public readership.” Here, what Kant primarily had in mind was the discussion of religious issues. His plea was mainly freedom of thought and expression in terms of religion. But the argument has applications also to all other issues of importance to man and citizen. The basic tone was optimistic: ”Do we live today in an enlightened age?” asked the philosopher and replied, ”No, but we live in the Enlightenment’s age.” He believed, in other words, that the obstacles to a free public use of reason and thus enlightenment were about to become fewer: ”In this regard, this age is the Enlightenment’s age, or Fredrik’s century.”

Can we believe the same about our own time? We know that in Sweden today it is more dangerous than it was in Kant’s time to publicly question religion in a way that the religious fanatics can see as blasphemous. When he spoke of ”Fredrik’s century,” he was referring, of course, to Fredrik II of Prussia, not Fredrik Reinfeldt. The question becomes whether we, in this century, can still maintain Kant’s optimism.

The threat comes not only from fanaticism, although the authorities’ own inability to counter this threat can be an issue of concern. The threat is even more so the quality of public discourse to which Kant ascribed such great importance. Kant envisioned a public where reasoning and argumentative scholars spread the use of reason and, through his writings, taught the readership in the art of thinking itself, to use their own reason. Thus he gave his definition to the concept of ‘public’ that was a product of the 1700s, ”The Age of Enlightenment”. Perhaps a reminiscence of that ideal remains, for example, in the Swedish public as late as fifty or seventy-five years ago, when editors who Torgny Segerstedt, Ivar Harrie or Herbert Tingsten could act on the public stage.

Tingsten reasons in the fourth part of his memoirs (My Life. Ten Years 1953-63), with his characteristic arrogance, about the chief editor’s freedom, saying:

When I write here […] about the chief editor’s freedom, the premise of the whole argument must be (a point which is not always clearly made) that he/she is developed intellectually, cognitively, stylistically, and preferably also morally. It is mainly through the appointment of prominent editors that owners recognise the principle of press freedom. At a certain degree of insignificance, talk of editor freedom becomes meaningless.

A discussion of this type seems today, almost fifty years later, quite implausible, perhaps even absurd. Tingsten enjoyed a publisher’s existence, which, by today’s standards, had an almost Olympic serenity. The owners of Dagens Nyheter he had to contend with were the Bonnier family, represented by mainly the highly cultured Tor Bonnier. The family obviously wanted to make money, but felt themselves as managers of a cultural legacy and a responsibility to the public as publishers. Tingsten spoke dismissively about the press freedom that was achieved on an exclusively commercial basis:

The same freedom can be achieved, when the owners are politically uninterested and just think about earning money through the newspaper, but the risk is here that the economic interest leads to a concern for everything eagerly, extremely and passionately, to a crude courting of readers through cheap means, and that the opinions, regarded as belonging to the outfit, become more or less elegant servile platitudes.

But the very question of ‘publishing’ and ‘freedom of expression’ in its relation to modernity’s ideals deserves a few words. Where is the crime itself, was the lack of the old outlook and is replaced by a new one? I think this takes place on a very fundamental level, almost on an epistemological one.

A rather natural way to think about things, which is also the universal pre-modern way, is to point out that truth is but one, though false opinions are many, and therefore the truth is what should be preached as clearly as possible, while false perceptions should be combated with all available means. Anyone who truly believes he/she has the truth becomes intolerant. We already know what the truth is, they are the many ‘opinions’ that are just a fog that obscures the eyes of the people. On the other hand, are we saying that the truth is still unknown or hidden, in which case the approach becomes somewhat different.

There is a duality here that is clearly visible, for example, in Plato’s dialogues. Wisdom seems most of the time to be something that we do not have, but are in search of. Socrates admits his own ignorance and sets out to seek knowledge. His looks for it in dialogue with others, by asking questions and testing answers in an ongoing discussion.

But there is in Plato another line of thought. According to the common “view” (“doxa”) the odious democracy is contrasted with ”insight” (”episteme”). Democracy, then, with its public square for public debate is valued low. Art and rhetoric are portrayed as an obstacle to truth. The philosopher’s rule, in accordance with reason and ”logos”, appears to be the desirable option.

In the Christian tradition, even in those influenced by Plato, the ambiguity was often replaced with clarity. If the Bible and the Christian revelation came from God, there is an obvious guiding principle. The many human perspectives will then appear as confusion and disorientation. So it is with, for example, Augustine in his ‘God state’. The ”Babylonian confusion” is associated specifically with Babylon, the Devil’s kingdom. In Jerusalem, the kingdom of God, there is only one perspective: a divine consensus. Everyone speaks the same language.

All kinds of religious fundamentalism, Jewish, Christian or Islamic, of course, consider their vision as the truth. Truth is one and indivisible. One can be for or against it. If one is against it, one’s motives can hardly be honourable. Such people are then consciously or unconsciously in the Devil’s service. If it happens unconsciously, if one is a victim of evil cunning and the art of dissimulation, one can still be saved. Otherwise, you are lost. This concept is so powerful and has such a strong psychological appeal that it can also be seen in modern contexts such as Marxist-Leninism, anti-fascism, feminism, anti-racism, environmentalism, peace activism and others. The existence of legitimate differences of opinion is denied in practice. Those who have a different opinion promote the bourgeoisie, fascism, men, race hatred, environmental degradation or warmongering. With them, one does not argue. The content of their arguments can be neglected. The important thing is to state why they have the perception they have, namely because they have chosen the path of capitalism, fascism, sexism, racism, environmental degradation or war.

The most obvious modern version of this concept is perhaps Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s doctrine of the ‘general will’, as outined in his The Social Contract. The infallible general will, is thought to be the spontaneous expression of people’s collective will. Rousseau talks about the unfortunate state of society, which sometimes occurs. When the state is weakened and ”individual interests become evident, and the small localities begin to influence the wider society, then the public interest becomes corrupted and they become opponents, the voices are no longer unanimous, the general will is no longer the will of all, there are contradictions, disputes, and the best the view is not accepted without controversy.” In this situation, the censorship of Rousseau can play an important role:

“Just as the general will is proclaimed by law, public opinion is proclaimed by censorship.” (Translation by Sven Åke Heed and Jan Stolpe.)

The idea is that censorship prevents views from being corrupted, and is therefore in the interest of public opinion.

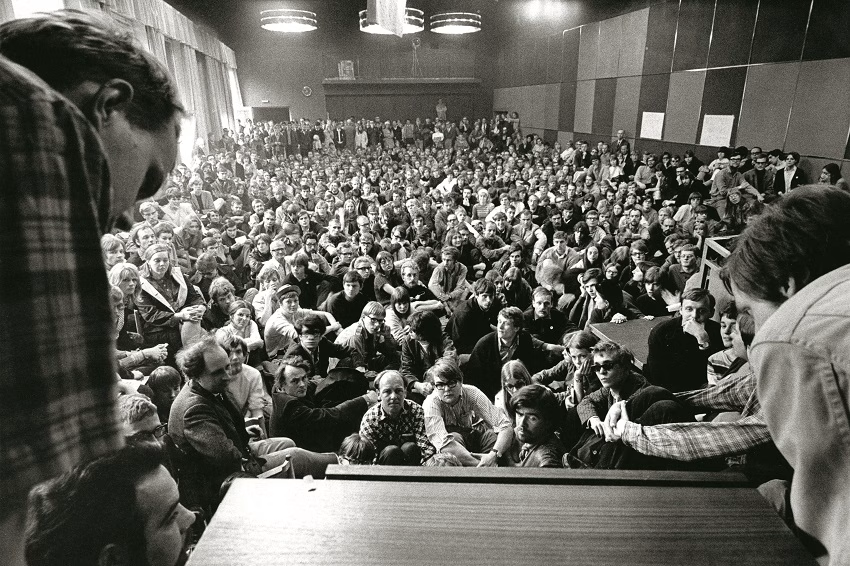

If you want to find a modern equivalent of Rousseau, one can think of Herbert Marcuse, who became the U.S. and West German student left’s prophet in the 1960s and ‘70s. In his One-Dimensional Man, Marcuse pointed out how far modern capitalist society was from real democracy:

The fact that the majority of people accept, and can be influenced to accept, such a society makes it no less irrational and reprehensible. The distinction between true and false consciousness, real and temporary interest is still meaningful. (Translation by Sven-Eric Liedman.)

In his essay ”Repressive Tolerance” Marcuse developed the idea of ??tolerance, which once had a liberating function, as now an instrument of oppression. The deeper tolerance that once characterised socialist society must not be indifferent with respect to what it tolerates. It must be intolerant of those that threaten people’s freedom and happiness, thus of the defenders of capitalism. True tolerance is not to “protect false words and unjust actions”. Liberating tolerance simply means ”intolerance of right-wing forces and tolerance of left-wing forces”.

Rousseau and Marcuse each represent, in their own way and time, a reaction against modernity, which means freedom of opinion, which dissolves the dense, warm, unanimous, non-alienated social community of which they dreamed. They turned against private special interests, against private opinions, against selfishness and individualism, and wanted to create a society where citizens rise within the community.

An ambiguity, in the way indicated from the start, is built into the notion of the ‘public opinion’. On the one hand, it is believed that the general will has a moral authority and is able to decide what is right and wrong. On the other hand, it consists of private opinions, of individual perspectives. A writer who put his finger on this ambiguity is the authoritarian-orientated German legal expert Carl Schmitt. ”Freedom of expression is freedom for individuals”, said Schmitt in his Diegeistesgeschichtlige Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus (The Current Spiritual State of Parliamentarism) of 1923.

Press freedom is the freedom for private owners to publish newspapers. But how can such a private freedom turned into a public one? How can the press be the third state power if it is not responsible for anyone but private owners? And besides, how can public discourse be the essence of democracy when everyone still needs to realise that discussion is not a way of making decisions but a way of putting them off?

One of the most influential modern texts on the public problem came with Jürgen Habermas’ book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (StrukturwandelderÖffentlichkeit) of 1962. Habermas starts, through the authors already mentioned (Locke, Rousseau, Kant, Schmitt), to address the public problem. From one point of view, one could say that he is trying to construct a response to Schmitt; from another, one could say he is trying to achieve a solution to the dilemma (free discussion versus a united general will, private versus public) that has always been central. Habermas’ background was in the ”Frankfurt School”, which also produced Marcuse. But Marcuse’s authoritarian solutions were too simple for Habermas.

The main issue for Habermas comes to something as seemingly abstract as truth. But Habermas connects the question of truth to the discourse and its rules, and therefore to the question of the public sphere and how it functions. Truth is for Habermas (as for Rousseau) the same as consensus, but (again as with Rousseau) not just any consensus. There are both true and false consensuses. True consensus can only emerge in a society free from oppression and violence, as the fruit of a free dialogue. True consensus presupposes a democratic socialist society and utopian realisation. The potential consensus that would arise in such a society is necessarily true.

False consensus is the result of oppression, says Habermas. The false consciousness derives from ‘impaired communication’. Not least Freud and psychoanalysis have taught us that communication can be ‘disturbed’. The manifest consciousness cannot be accepted in good faith. It must be exposed to a rigorous interpretation. It may have been influenced by unconscious, unrecognised, causal factors. Slips of the tongue and misconceptions are just some of the most obvious examples. This psychological effect transfers Habermas to an ideological level.

A social consciousness is determined by much more than the rules of rational communication. Historically, we know it is rarely (if ever) a rational discussion between equal partners, where it is only an argument’s probative power that decides. Authority, power, wealth and more usually play a larger role in determining the progress of society. The strong win, not because they are right, but because they are strong. In a class-based society, in every society where the strong stands against the weak, this must apply, so goes the argument. It all leads to Habermas’ idea of ??a ‘domination-free communication’, which is thought to be possible only in a classless, socialist society. Only in such a society can true consciousness occur, a true public, if you will; an ideal society.

Habermas ends, in other words, at approximately the same point as Rousseau or Marcuse, in a sort of socialist utopia. But he believes, at least, that this cannot be reached without discussion. He takes a detour for a discussion of discourse conditions. But is this sufficient to nullify the opposition that Carl Schmitt observed between democracy (in Rousseau’s sense) and the parliamentary system in the public sphere characterised by conflicts of interest and differing opinions? I do not think so. Habermas’ conception gives no real room for parliamentarism and publishing’s basic idea, namely that there may be legitimate differences of opinion; this insight, such as John Stuart Mill developed in On Liberty, he could never reach. But he pointed out, at least, like Schmitt previously did in another way, the problems inherent in the liberal conception.

The liberal conception of the public, as well as the liberal conception of society, is based on anarchy and lands in a contract. The unbearable state of war of everyone against everyone enforces the social contract, according to classical liberal theory. The door of reason is clear. A contract requires a regulatory environment, it implies the existence of a contract law that defines what a contract is and in what way it binds the parties. But contract law can only exist in a society. Contracts can only be created in a state of society, never in a state of nature. Something similar can be said for society. Habermas was by no means the first person to bring this up, but he had the merit of inculcating it with great force. Society does not require consensus and does not lead to consensus. But it requires at least a consensus on the rules of conversation. And it requires a willingness to agree at least in the sense that each participant in an argument tries to reach a consensus about his/her own position. Society aims to enable participants to come up with something, sometimes even to a decision.

Cicero and other ancient thinkers have long been clear about this. Cicero termed the state res publica (the public affair). He criticised the tyrant who regards the state as his own private affair. Cicero also stressed society’s roll in creating a social community and culture. Rhetoric and philosophy should be combined, not behave like enemies. Power and justice, persuasive and convincing should be united. For Cicero, Rome appeared, during the Republic’s time at least, as an approximation of that ideal.

Can it be realised under modern conditions? A public sphere and publishing can occur only in this ambiguity. Publishing – whether books, newspapers, broadcast media, social media or online are the central arena – needs to exist in a balance of effective power (political and market forces) and the ideal of a society where the weight of arguments and the search for truth decides.

There is no domination-free communication and never will be, if not in Jerusalem then beyond the grave, as Augustine said. Nor is there any consensus that may occur by means other than repression. But there may be a more or less open debate. There may be a common environment. There may be differences of opinion. There may be a fruitful conversation. There can, in short, be civilisation and all that makes civilisation possible. Necessity’s weight cannot be disregarded. There is no leap into the realm of freedom. But freedom can, in the best-case scenario, at least for a moment, be achieved in actual conversation. And conversations, both private and public, are necessary conditions for the perpetuation of society. Neither Cicero nor Habermas were mistaken in seeing society as a communicative community. Nor was Kant wrong when he assigned a public use of the word and assigned reason a strategic role in designing a modernity of responsible people.

Redan prenumerant?

Logga inAxess Digital för 59 kr/mån

Allt innehåll. Alltid nära till hands.

- Full tillgång till allt innehåll på axess.se.

- Tillgång till vårt magasinarkiv

- Nyhetsbrev direkt till din inbox